RESEARCH PROJECTS

UNOBTRUSIVELY MEASURING CULTURE

To be resilient, organisations must assess their cultures and evaluate the workplace norms and behaviours that strengthen or undermine effective risk management. Yet, this process can be paradoxical, because the cultural phenomena that cause problems in managing risk (e.g., normalisation of poor standards, being silenced) often make traditional methods for measuring culture (e.g., surveys) unreliable and even misleading. To resolve this, we developed and tested the idea of “unobtrusive indicators of culture”: measures of culture drawn from everyday behaviours in organisations that provide both quantitative and qualitative insight on the values that guide people.

Based on a systematic review of the literature and analysis of publicly available data on major companies, we developed ‘unobtrusive indicators of culture’ (UICs): these use AI-algorithms to analyse textual data created through either everyday activity in organisations (e.g., speeches, conversations, incident reports), or unvarnished and naturally occurring descriptions of experiences of an organisation (e.g., employee feedback, complaints). The AI-algorithms produce both quantitative measurements of culture (e.g., scaling the presence of organisational norms), and surface high-relevance segments of text for qualitative analysis and explanation and exploration of cultural phenomena. We collected data from hundreds of companies on the MSCI Europe Index, and also from healthcare institutions, and examined whether organisational culture could be reliably assessed and distinguished with the UICs, and used to explain risk outcomes. We found, across diverse domains, that the UICs not only provide valid data for benchmarking and assessing the cultural health of organisations, but predict outcomes such as hospital mortality, corporate scandals, and financial performance. This work suggests that theory and research on culture may benefit from moving away froma focus on shared norms and surveys, and instead should study culture through analysing the common and persistent patterns of thinking and behaviour that make culture and are embedded into the digital data of organisations. Our more recent work on this area focusses on the use of AI Large Language Models (e.g., ChatGPT) to assess textual data, for instance live dialogue, and provide insight on the cultural phenomena it reveals. Please see the following publications: Reader et al., 2020; Reader & Gillespie., 2022; Gillespie & Reader, 2023; Reader & Gillespie, 2024

CORRECTIVE CULTURE AND RESILIENCE

Organisational culture can be both the cause of institutional failures such as accidents and corporate scandals, and a source of resilience for managing threats and disruptions (e.g., crises, COVID-19). To explain the dual role of culture in managing risk, and explain the cultural processes needed in organisations for preventing incidents and coping with ‘unknown unknowns’, we developed the theories of ‘corrective culture’ and ‘resilient culture’. These model the specific norms and behaviours that guide processes in organisations for tackling problems, learning from mistakes, and adapting to the unexpected.

We initially undertook a systematic review of accident analyses, and observed that within the academic literature, culture is found to cause institutional failures in two ways: first, it underlies the behavioural problems that create risk (‘causal culture’), and second, it prevents the corrective actions needed to fix these (‘corrective culture’). Whilst the former is well understood within the literature (e.g., embedded in concepts such as ‘safety culture’ or ‘ethical culture’), the latter is poorly understood. We addressed this, and expanded the concept of ‘correct culture’ throughan AI-augmented analysis of 54 UK judge-led public inquiries into major institutional failures (e.g., in healthcare, banking, energy). The analysis showed that, regardless of the causes, all failures featured organisations with a deeply embedded culture of having “problems in dealing with problems” (i.e., corrective culture), and this manifested in sequential and worsening breakdowns in cultural processes for identifying, understanding, and addressing risk, with these preventing making institutional learning on risk. We then investigated the opposite phenomena – how culture enables organisations to adapt when faced with unexpected threats and disruptions – through a systematic literature review of research on resilience. This showed how organisations that are successful in navigating uncertain and hazardous situations have a ‘resilient culture’: this pertains to shared norms and common practices that foster capabilities for preparing, monitoring, action, and learning, and combine to create a culture in which people are able and guided to engage in the adaptive processes needed for managing threats and disruptions. Please see the following publications: Hald et al, 2021; Hald et al., 2023; Hald et al., 2024

LEARNING FROM FEEDBACK IN ORGANISATIONS

Feedback from external stakeholders (e.g., service-users and citizens) to organisations is potentially a valuable source of resilience because it can provide information on problems observed in risk management (e.g., system failures). Yet, in domains such as healthcare, external feedback is often not learnt from because of its complexity (e.g., the NHS 200,000 written complaints annually) and a culture of viewing it as not valid. To improve how organisations learn from external feedback, and test its value for manging risk, we developed the Healthcare Complaints Analysis Tool (HCAT).

HCAT is a freely available framework that guides systematic coding on the nature and severity of written complaints sent to hospitals by patients and families. It was developed and tested through a systematic review and analysis of several thousand complaints, with the goal being to i) provide a practical tool for hospitals to learn from the voluminous and detailed feedback sent to them by patients and families, and ii) generate theory and insight on how complaints from stakeholders can improve risk in organisations. Our analysis found that HCAT allowed hospitals to systematically extract data about risk contained with complaints (e.g., on medical errors, system problems), with patient and family feedback predicting outcomes such as hospital mortality with greater validity than internal data (e.g., on safety incidents), and when analysed and learnt from, providing the basis for interventions to improve risk management. Our analysis also explained how external feedback aids organisational learning: specifically, because external stakeholders often encounter the sharp-end problems of organisations, pick-up on ‘blindspots’ in risk management (e.g., unseen communication gaps between units), and are less constrained by institutional norms (e.g., for criticising management), they can challenge organisational complacency and reveal unrecognised or unresolved problems in risk management. For organisations therefore, developing a culture learning from stakeholder feedback is potentially transformative as it can enable the early detection of problems in risk management, and generate crucial – and freely given – data for learning and improvement. We have adapted HCAT to other domains (e.g., policing, justice), and an automated version using AI has been developed and tested on online feedback from patients and families to hospitals. Please see the following publications: Reader et al., 2014; Gillespie & Reader, 2016; Reader & Gillespie, 2021; Van Dael et al., 2022; and also a REF2021 impact case study.

VOICE AND LISTENING IN ORGANISATIONS

Good communication underpins risk management because it is the mechanism through which people create the shared understanding and joint action needed to prevent incidents and ensure resilience (e.g., correcting mistakes, responding to new threats). Yet, accident analyses often find that people fail to voice on risk, and that, when they do speak-up, they are not listened to by colleagues or organisations. Our research investigated the cultural causes of this, and established a framework of effective voice and listening behaviours in organisations.

To investigate the cultural factors that influence voicing and listening in organisations we initially undertook a series of accident analyses, literature reviews, dialogical analyses, and survey studies in domains such as oil and gas, aviation, and healthcare. We found engagement in voice to be determined by factors such as psychological safety, hierarchical structures and power, quality of reporting systems, and interpersonal skills, and listening to be shaped by defensiveness, perceptions of voicer credibility, bureaucracy, empathy, and training. We then attempted to develop a framework for measuring voice and listening behaviour in organisations, and explain their link to risk outcomes. To create a framework for assessing voice behaviour, we developed a laboratory scenario (“walking the plank”) that presented participants with a clearly unsafe situation designed to elicit speaking-up behaviours. Whilst two thirds of people voiced, they often did so in a ‘muted’ fashion whereby they indirectly raised concerns (e.g., by asking a question) and hoped others would, akin to fishing, ‘get a bite’ on the problem. We found that as people became more uncertain or hesitant in speaking-up, their voicing behaviours became more muted, which made it hard for listeners to hear and address concerns. This observation is important for risk management in organisations, because it shows that, to identify and address risks before they become truly dangerous (i.e., when they are unclear and emerging), they must focus on ‘unmuting’ voice rather than simply encouraging speaking-up. Organisations also need to ensure they are effective at listening, as voice acts cannot be impactful without this, and we investigated this through analysing transcripts of airline crews responding to voice acts prior to hundreds of accidents and near-misses. We conceptualized effective listening as behavioural engagement with voice (but not necessarily agreement), with this manifesting as air crews acting on voice or trying to determine whether a voice act had occurred and the reasons for it. Please see the following publications: Reader et al., 2007; Reader & O’Connor, 2014; Grailey et al., 2021; Noort et al., 2021; Noort et al., 2021; Reader, 2022; Pandolfo et al., 2024.

CULTURE AND CORPORATE SCANDALS

Corporate scandals (e.g., fraud) are often blamed on the behaviour of rogue employees, yet organisational culture creates the environment in which misconduct can occur. We developed this idea through an AI-based investigation of organisational culture in over 200 companies, and investigated whether companies that develop a strong ‘target pressure culture’ are more likely to experience corporate scandals due to them making poor conduct permissible or necessary.

We gathered anonymous employee online reviews (71,830 reviews, containing 4,356,105 words) about working in major European companies, and developed an AI-algorithm that analysed the textual data to measure the degree to which norms for target pressure were highly salient amongst employees (i.e., at the forefront of people’s minds). We supposed these data would be valuable because they provide unvarnished and large-scale qualitative information about employee experiences in companies. We found that whilst some target pressure is motivating for employees, where it becomes excessive organisations develop a ‘strong target pressure culture’ that is characterised by overly ambitious targets that are beyond employees, highly consequential targets that generate strain, and expediency in achieving targets which encouraged an “ends justify the means” mindset. A strong target pressure culture was associated with greater risk of corporate scandals, and this is because it creates a ‘pressure cooker’ environment that promotes, incentivizes, and normalizes deviant or risky behaviour, and implicitly undermines organisational values on the importance of safety and ethics. Please see the following publications: Reader & Gillespie., 2024.

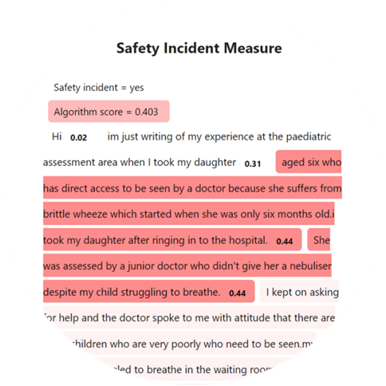

DETECTING OVERLOOKED INCIDENTS

Detecting safety incidents is challenging because staff are inconsistent in their reporting. As an alternative, we used AI to detect safety incidents patients’ online narrative feedback. While staff-reported incidents were found to have no association with hospital mortality rates, we found a strong and consistent association between AI-detected incidents in the patient narratives and hospital mortality rates.

Safety reporting systems are widely used to detect incidents. But, their effectiveness is undermined if staff do not notice or report incidents. Patients, on the other hand, may provide valuable date because they: experience the consequences, are highly motivated, independent of the organizational culture, can report without fear of consequence. We analysed 146,000 patient narratives from 134 NHS Trusts using an algorithm to detect patient-reported incidents. This measure of patient-reported incidents was independent of staff-reported incidents, and had a strong and consistent association with hospital mortality rates (unlike staff-reported incidents). We argue that online stakeholder feedback is akin to a safety valve; being independent and unconstrained, it provides an outlet for reporting safety issues that may have been unnoticed or unresolved within formal channels. This provides supporting evidence for our previous research on the value of patient complaints in detecting unsafe care. Please see the following publications: Gillespie & Reader, 2016; Gillespie & Reader, 2018; Reader & Gillespie, 2022.

A SYSTEM APPROACH TO SAFETY CULTURE

The safety of international air travel relies upon aviation organisations – including air traffic control, airlines, airports, and aircraft manufacturers – developing a system-wide ‘safety culture’ in which norms and practices support safety. Yet, a singular and valid global approach to assessing safety culture in aviation is lacking, and this is needed to ensure that diverse organisations operating in diverse contexts and with diverse workforces foster the coherent culture needed for preventing accidents. To address this, we developed, tested, and rolled-out a methodology for measuring and improving safety culture across the European aviation industry.

Starting with air traffic control, and collaborating with EUROCONTROL (which coordinates air traffic in Europe), we developed and tested a bespoke survey and qualitative investigation methodology for assessing safety culture. Over 40 international air traffic providers and 50000 people participated in the safety culture assessment process: this work not only led to improvement in safety management in European aviation, but also established the subtle relationship between national culture and safety culture, and the role of identity in shaping how people understand culture. This was crucial for enabling us to understand the system factors that shape safety culture, for example on how occupational roles and societal norms on power distance (i.e., the power authority over those in junior positions) shape willingness to speak-up on risk, and develop tailored interventions to improve culture. Additionally, benchmarking air traffic control centres with strong or weak safety cultures, we were able to identify potential weaknesses in aviation systems, explain safety lapses, and encourage learning between providers. Subsequent research extended and validated the safety culture methodology with airlines, manufacturing, airports, and service companies. This led to the formalisation of a ‘system’ approach whereby culture is measured across all organisations in the aviation network simultaneously, and interdependencies that have the potential to create risk (e.g., misalignments between the culture of airlines and ground handling companies) are identified. This work advanced theory on culture and risk by recognising that, in domains such as aviation, the cultures of organisations are intertwined with one another and must be understood as a delicate and dynamic ecosystem: for instance, the safety of an airline hinges not only on its safety culture, but that of the organisations that maintain planes, manage infrastructure, guide aircraft, and undertake security. Please see the following publications: Mearns et al., 2013; Reader et al., 2015; Noort et al., 2016; Tear et al., 2021, , and also a REF2021 impact case study.

CULTURE AND SAFETY CITIZENSHIP

Safety citizenship behaviours by employees that go ‘above and beyond’ are often essential to effective risk management in organisations: for example, suggesting improvements, helping others, and being conscientious and vigilant. We investigated the cultural factors that underlie citizenship behaviour, and how these contribute to safety outcomes.

Drawing upon social exchange theory, we explored whether citizenship behaviours for improving safety were engendered in organisational cultures that supported employees and invested in their well-being. We tested this idea in the oil and gas sector, and found that actions by energy companies to improve the health of oil rig employees resulted in reciprocal efforts by workers to improve the safety of offshore platforms, with employees viewing company efforts to support their well-being as a signal of their obligations to them, and then responding in-kind with citizenship. Building on this observation, we undertook further research on the cultural antecedents of citizenship in aviation, and this showed how, when organisations foster a shared identity on safety with employees (e.g., on commitment to values and the activities of occupational groups), this increases employee motivation to engage in citizenship behaviours that support the identity. Please see the following publications: Reader et al., 2017; Tear et al., 2023.

Environmental Culture in Organisations (ECO) framework

Large organisations and their members can play an instrumental role in helping to address environmental challenges such as climate change. Yet, research on sustainability often focuses on individual beliefs rather than the culture of organisations. To examine how organisations can develop cultures that guide and support pro-environmental behaviour in the workplace, we created and validated the Environmental Culture in Organisations (ECO) tool.

Drawing upon theory for organisational culture and predictors of workplace pro-environmental behaviours, we developed the 25-item Environmental Culture in Organisations (ECO) scale. This assesses an organisation’s culture for environmental sustainability, and breaks down culture into component organisational aspects (e.g., the actions of leaders, norms among coworkers etc). We tested the tool through a series of validation studies (n=2500+ participants), and found it to have a coherent structure, convergent and discriminant validity, and to predict workplace pro-environment actions. Accordingly, we suppose that ECO can be used to evaluate whether organisations have a culture that supports sustainability, and to provide insight and guide institutional initiatives for promoting pro-environmental behaviour. Please see: Sabherwal et al., 2024

HUMAN FACTORS IN FINANCE

It is increasingly recognised that major failures in financial organisations have similar causes to those in domains such as nuclear power, healthcare, or aviation: namely, ‘human factors’ problems (e.g., errors in decision-making or teamwork) that lead to lapses in risk management. Yet, unlike safety-critical domains, little is known about the population of errors in financial trading, or how they can be prevented from occurring or causing harm. We investigated this by determining the nature and prevalence of risk incidents in financial trading, and establishing their human factors and cultural causes.

We undertook our research on the trading floor of a major commodities firm, and, based on accident reporting systems in aviation, developed and established an incident reporting system through which traders could report on errors (e.g., breaching trading limits, incorrect volumes) made by themselves of others. Over a period of two years, data on trading errors were captured and learnt from in order to improve performance. Analysis of this data, which was both narrative and numerical, revealed that over two years an error occurred in nearly 750 trades (approximately 1% of all transactions). The cost of errors could be substantial – for example when accidently “longing” rather than “shorting” a product – and most were caused by problems in non-technical skills and issues in human computer interaction. Subsequent research found that where teams had a collaborative culture in which people engaged in ‘backup behaviours’ to support one another (fixing mistakes), and raise concerns over behavioural and system problems (e.g., on poor design), this prevented errors, losses, and incidents. An analysis of major trading incidents in banks showed how problems in safety culture, for example management not investing in systems and listening to concerns from staff, teams working in silos and unaware of their interdependencies, people downplaying or not assessing risk, and conflicting targets and rules, often underlies human factors issues and poor conduct. Please see the following publications: Leaver & Reader, 2016; Leaver & Reader, 2016; Leaver et al. 2018; Leaver & Reader, 2019.

TEAMWORK AND DECISION-MAKING

The influence of culture on managing risk in organisations is often most apparent in situations where teams must collaborate to make highly consequential decisions (e.g., during a crisis). To understand what underlies and distinguishes teams that are successful at this, we investigated the teamwork processes that underlie effective decision-making in acute and emergency medical teams.

We undertook a series of observational, survey, vignette, and interview studies to investigate the skills and group dynamics that underlie effective decision-making in the intensive care unit (ICU). In terms of teamwork, the development of open communication channels that enabled the building of ‘shared situation awareness’ was found to enable teams to make better decisions on patients due to members both forming a coherent ‘mental picture’ of the patients they treat (e.g., through information sharing), and also cultivating an understanding of interdependencies between team members and how each would contribute to the enactment of decision-making. Leadership by senior doctors was key to setting the culture of teams, for instance building psychological safety, soliciting contributions for all members, and setting clear directions, and a norm of ‘adaptability’ where teams could shift from being more democratic (e.g., junior doctors leading patient diagnoses) to more autocratic (e.g., senior clinicians directing responses to a major crisis) was crucial for controlling risk and avoiding errors. Moreover, the ability of teams to avoid inertia, make risk trade-offs, and combine experience and foster innovative thinking was crucial for overcoming ‘impossible decisions’ where no obvious course of action was apparent: for example, where an intensive care unit was overloaded with patients, or treatments had potential to cause harm to patients. Please see the following publications: Reader et al, 2007; Reader et al, 2011; Reader et al., 2011; Reader et al., 2018; Pandolfo et al., 2022.

LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS AND PSYCHOLOGY

Recent developments in large language models have created huge opportunities for psychological research on organisational culture and risk. We can potentially use LLM applications such as ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude to AI to codify, ask questions, and draw meaning from qualitative datasets that are beyond human comprehension: for example, large-scale textual data from online discussions, service user feedback, or safety incidents. Our research examines how LLMs might be used to analyse such data.

Our research has focussed on developing and testing protocols for using LLM prompts to generate meaningful and valid psychological observations from qualitative data, and to ensure that tools are used in a robust and ethical manner. Moreover, we have found that LLMs can not only codify different forms of qualitative data (e.g. internet forums, diaries, complaints) in a similar and reliable way to humans, but can also help to generate new insights and develop concepts through pushing back and observing when data is surprising or does not fit theoretical assumptions. Due to this, and the gains of speed and scale that LLMs provide, we suppose AI-augmented analyses of textual data have potential to fundamentally change qualitative research and risk analysis. Publications are forthcoming.